Shraga Biran: Painting Time | Ron Bartos

What is the time in which one painting or another by Shraga Biran was created? We may answer that the painting was painted at a certain time, for instance in a particular year or even on an exact date. We could also specify the length of time it took to complete said painting. If we wish to know the painting’s time we could also point to the zeitgeist that imbues it, that is to say, to the degree of its belonging to its time or the influence of a specific period on it. But all these still do not offer an adequate answer to the question: what is the time in which the painting was created, what is the time of Biran’s painting? And so, this paper, which is dedicated to the artistic practice of Shraga Biran, will revolve around the root of the Hebrew word for time – zman, זְמַן – and the concept of time, and these will serve as a pathway into his art.

Invitation

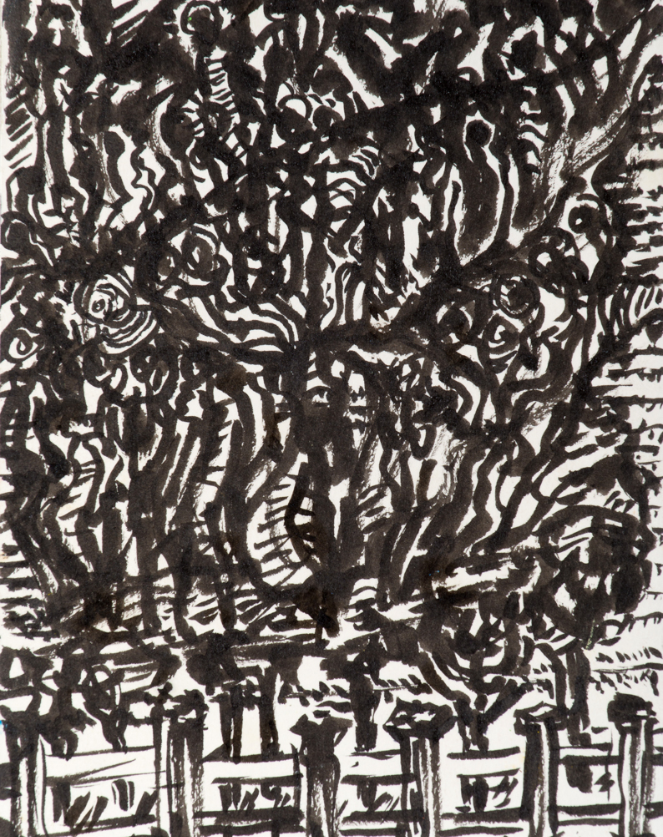

The hand holds the pen to the cardboard and starts drawing in blue ink the border that will serve as the painting’s frame. This is a fast line, whose pauses are determined while moving forward. And so, the border demarcates a plot of paper, which begins to fill with the same scribbled and urgent line. The composition takes shape and conjures up a landscape view, since it is divided into a strip of sky above and a strip of land below. The lower strip of painting is populated by a cluster of spheres that look like a crowd huddled to witness an unknown event – a demonstration of the forces of nature, a passing parade, an inferno, an apocalypse – all these are viable options.

When the hand puts down the pen, it draws back to reveal the inscription “Yad Vashem – The Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority.” This is an invitation, an invitation to the museum’s event, which in Biran’s hands became a fortuitous surface for a painting that cancels out the invitation’s function and extracts it from the time to which it is anchored and to which it points. But it is also an invitation to a tempestuous, passionate, and creative inner world, at times even to the soul, and most certainly to the art of Biran. This is not the public, well known Shraga Biran, the lawyer and entrepreneur, but rather the private, unknown, hidden Shraga Biran, the artist who keeps to himself among the tools of his art, and continues to paint at all times.

Painting Time

The invitation (including the above-mentioned invitation) stands at the center of a triangle: inviter-time-invited (and in Hebrew: מזמין-זמן-מוזמן that are all linked by the root Z.M.N.). The invitation is sent by the inviter to an invitee, inviting them to a certain time (and place). The three are interdependent, so if one is absent or deviates from its function, the event cannot take place as planned or indeed at all. This triangle calls to mind the artistic triangle of artist-artwork-observer, which establishes the equation of art, where should one of its sides falter, it would also inevitably disrupt the artistic-cultural mechanism. The comparison between the temporal triangle and the artistic triangle creates an equation between art and time, that is to say, painting is time, and time is painting.

The philosopher Henri Bergson distinguished between the mechanistic, imagined time of physics and the actual lived time as we experience it. While the imaginary time can be divided and measured and the movements in it can be calculated in advance (given sufficient data), the movements in the actual lived time are the outcome of continuous and unpredictable creativity. Bergson called this time “durée” (duration) due to its indivisible quality, which carries out an organic creative activity that develops over a period of time. Continuity is therefore a time of creative flow, of transformation and metamorphosis, of natural, painting movements, and its perception is not cerebral but rather intuitive.

The painting is a capsule that holds a “duration”, a testament to the time and process of creation. The grasp of painting in time is abstract, but it also has real, visual expressions embodied in the work itself. If we turned to look at Biran’s paintings we would find: increasing density; Movements of ascension, decline, or inwards perspective; Metamorphoses and incarnations that transform angels into human beings, humans into crowds, crowds into pests, as well as land into heaven, moon into sun, and invitation into painting. All these and other traces in the various paintings attest to the creative time and the “duration”, the time of the painting and painting as time.

Tempo

In Italian, “tempo” means time, but tempo is also a musical term that defines the speed of music, meaning, its movement and the pace at which it is played, and in effect: the time of the music. Figuratively, we could say that one of the facets of the time of the painting is its rhythm – or tempo, and as one can easily see, Shraga Biran’s painting is a highly rhythmic painting.

We may also consider the style of Biran’s art through the rhythm of the painting, and the Biranesque rhythm is quite distinct: the scribbled line is fast and energetic, creating a sense of urgency – a feeling of shortness of time. This aspect is amplified by the density of the composition and its elements, so that the shortness of time is also manifested in shortness of space. Usually, the space of the painting is filled to the brim with serpentine elements – a “Laocoonesque painting” if you will, tangled and entwined with a vigorous Baroque expressiveness.

The tempo of the painting also serves as the basis for the multiplication of rhythms. Polyrhythm is the simultaneous use of two or more rhythms, and Biran’s painting is often a polyrhythmic arena of multiple painting rhythms. The quick line, the Laocoonesque movement, the automatic drawing, the accelerated perspective, the split composition (into a diptych or triptych), the mechanism of concealment and the mechanism of revealment, the morphology of images, the density of objects and the moments of emptiness are all subject to the tempos of the painting. And even when they are disparate or conflicting, this does not prevent them from merging harmoniously into Biran’s painting time.

Opportunism

“To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven” this is how Ecclesiastes starts his speech, teaching us that each of man’s acts and desires has its right time and timing. Ecclesiastes goes on to detail: “A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted […] A time to love, and a time to hate; a time of war, and a time of peace.” In this list of contradictions, Ecclesiastes encompasses man’s life from beginning to end, with the exception of the time to create – the time of painting. In his poem, “A Man in His Life,” Yehuda Amichai responds to Ecclesiastes with the statement that there is no time for everything but rather there is everything at once: “A man doesn’t have time in his life / to have time for everything. / He doesn’t have seasons enough to have / a season for every purpose. Ecclesiastes / Was wrong about that. // A man needs to love and to hate at the same moment, / to laugh and cry with the same eyes […]. Similarly, Shraga Biran does not have painting time. His paintings are created at all times: on an invitation or envelope after opening the mail, on a napkin or a restaurant menu during a meal, on a program at a concert, on a Christian icon after a trip to the Old City, on a piece of paper while talking or at a meeting, and also while driving, waiting, contemplating, pondering, and thinking – at all times. Thus, in the absence of time and at all times, his paintings have been painted and accumulated to many hundreds.

Returning to the question that opened this text – what is the time in which Shraga Biran’s painting was created? – we could go on to reply: the time of opportunity. Biran’s worldview places great emphasis on opportunity, and sees the opportunistic action and its outcome as manifesting the freedom of the free man, who has the power to decide his own fate. In his book Opportunism: How to Change the World – One Idea at a Time, Biran expounded his socio-economic-philosophical doctrine by formulating an innovative position on opportunism as a positive and creative value. Biran asserted that there is “a need to identify the opportunities, to connect and activate all the unexpected, singular, and creative acts of combination and dissolution.” Opportunism, therefore, is a driving force in Biran’s life and work, and more than any other time serves as Biran’s opportune painting time.

Opportunism underscores the nature and singularity of the subject, because it allows each person to act in his own individual way when faced with a similar reality, meaning, to realize himself by identifying the possibilities held in reality and utilizing them as he wishes. “The encounter with a planned or random set of circumstances and turning them into opportunities,” writes Biran in his book, “is man’s masterpiece.” As such, the opportunistic painting, namely, the opportunistic creation, becomes singular and inseparable from life.

Thus, Biran’s paintings are imbued with the reality of his everyday life as an echo of the time of the painting, interwoven into Biran’s timeline. From this perspective, the opportunistic creation attests to Biran’s experiences, as a man as and a painter: where he was while painting, the company he was at the time, the music that played in the background (often on the stage in front of him), the flavors and smells he sensed, the setting of the house or the city or the landscape that surrounded it, the books he read, the stream of consciousness that coursed through his mind, and the creative process as it unfolded. And when the time of painting occurs, not only is it not impervious to all the thoughts, sensations, and events that take place along the timeline, it even embraces them because they are the forces of reality that summoned the opportunity to create. Reality, then, is expressed and offers the opportunity for creative and subjective act.

The opportunism of painting leaves its safe harbor of time, if we will – the same port or portus to which sailors looked when they prayed to the Roman god of ports Portunus on their journey “towards the port” (ob portus). But among the seafarers, there were also those who set their destination according to the direction of the occasional breeze and simply took the opportunity to sail. They were called opportunists. Thus, Biran’s opportunistic painting sets sail from the shackles of time and reality on the waves of creative possibilities held in the time of the painting.

About

Shraga P. Biran (1932) is a lawyer, entrepreneur, author, and painter. He lives and works in Jerusalem.

Biran studied art at Kibbutzim College in 1951-1953, and with painter Yehezkel Streichman. He has kept painting ever since, but this aspect of his life is not widely known.

Biran is the author of Shall Reap in Tears (HaKibbutz HaMeuhad, 2000) and Opportunism: How to Change the World – One Idea at a Time, which was also published in English by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York in 2011 and in Chinese by China Social Science Press in 2017.

Impressions, the previous catalogue devoted to Biran’s work, was written by art historian Dr. Gideon Ofrat, and published in 2012.

(1) See Gideon Ofrat, “Laocoonesque Drawing,” Shraga Biran: Impressions, Jerusalem, 2012.

(2) Ecclesiastes 3:1.

(3) Ecclesiastes 3:2-8.

(4) Yehuda Amichai, A Man in His Life, translation taken from the University of Mexico Website: phys.unm.edu/~tw/fas/yits/archive/amichai_amaninhislife.html

(5) Shraga Biran, Opportunism: How to Change the World – One Idea at a Time, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011).

(6) Ibid.